Plot Points and the Inciting Incident

Understanding when the problem of the story starts sets an author straight.

Plot points can sometimes be difficult to pick out, especially when there is confusion as to the purpose of such a device in a story. If one accepts the idea that stories are about solving problems, the reason for Inciting Incidents and Act Turns becomes all too clear.

Every problem has its own genesis, a moment at which the balance is tipped and the previous sense of oneness is lost. With separation comes the awareness of an inequity, and a desire to return back to a state of parity. Every problem has a solution, and a story explores that process of trying to attain resolution.

In a story, this Opening Event--or beginning of a story--is commonly referred to as the Inciting Incident.

The Exciting Incident

The Inciting Incident (or "exciting incident" as my brother once referred to it) is the event or decision that begins a story's problem. Everything up and until that moment is Backstory; everything after is "the story." Before this moment there is an equilibrium, a relative peace that the characters in a story have grown accustomed to. This incisive moment, or plot point occurs and upsets the balance of things. Suddenly there is a problem to be solved.

Stories are about solving problems. Sometimes they are solved, as is the case with Star Wars, Casablanca or Inception. Other times, as with stories like Hamlet, Amadeus or Se7en, they aren't. Regardless of outcome, this Inciting Incident gets the ball rolling by introducing an inequity into the lives of the characters that inhabit the story. The Protagonist seeks the solution, the Antagonist seeks to prevent it.

Every story works this way.

The Reason for Plot Points

The two central objective characters, Protagonist and Antagonist, battle it out until approximately one-quarter of a way into a story, some other event or decision occurs that spins the story into a brand new direction. This second plot point is referred to as the First Act Turn as it turns the story from the First Act into the Second. This is a further development of the problem, not the beginning of a problem.

Other plot points--the Mid-Point and Second Act Turn--continue to escalate the issues surrounding the efforts to resolve the problem until finally, the Concluding Event, or Final Plot Point, ends the story. As mentioned above, this does not necessarily mean the problem has been solved. It simply means that the efforts that were undertaken by the Protagonist have come to their natural end as every resource has been exhausted.

These plot points naturally split a story into four parts. For fans of Aristotle, the first part is the Beginning, the second two are the Middle and the third is the Ending. There is a meaningful reason why there are four parts. In short, for every problem there are four basic contexts from which you can explore the way to solve a problem. Once you have explored all four contexts, the story is over. Any continuation would simply be a rehash of something that has already been investigated.

The most important thing to take away from all of this is that the First Act Turn is NOT the Inciting Incident. This is a common mistake by many first time writers, and is generally caused by a lack of understanding exactly why these plot points exist in the first place. One plot point starts the problems, the other furthers the complications of said problem.

Inciting Incidents and First Act Turns

The following is a list of great stories with their corresponding Inciting Incidents and First Act Turning Points. The numbers provided are either based on page numbers, Kindle percentages or minutes depending on what source material was easily accessible.

For those who don't know, the general idea is that one page of a screenplay generally lines up with one minute of screen time. A 120 page screenplay often lasts two hours on screen. or 120 minutes. Thus, the Inciting Incident would occur on or near page 0, while the First Act Turn would happen somewhere near page 30 (out of 120).1 If we're talking percentages, that would be about one-quarter of the way into a story.

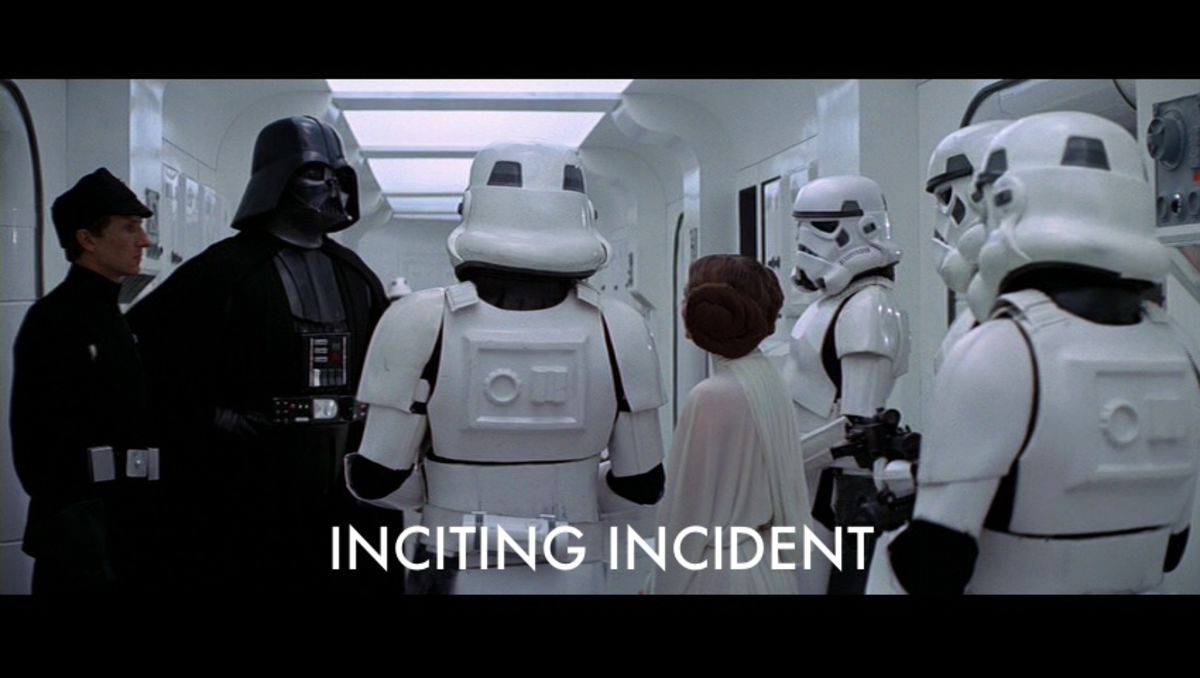

Star Wars

The Inciting Incident of Star Wars is Darth Vader's attack on Princess Leia's ship (1/120). While there was a civil war going on prior to this event, it isn't until the Empire shows its true colors by illegally boarding a ship purported to be on a "diplomatic mission" that the real problems of the story begin. The Empire has grown ruthless in its efforts to contain any rebellion, this inciting event is only the beginning of many more to come.

The First Act Turn begins with the Empire's sinister agents attack on peaceful Jawas and ends with their barbeque of Uncle Owen and Aunt Beru (30-31/120). Suddenly, what began as a simple conflict over jurisdiction has now turned into an all-out rampage that affects even the most remote and more importantly, innocent, members of the galaxy. The problem has grown in its potential for even greater conflict.

The order of Objective Story Transits found in Subtxt matches the changing concerns of the Objective Characters in Star Wars. The Inciting Incident (first Story Driver) is an illegal act of boarding, creating conflict through Doing. The attack on Luke's relatives shifts the concern from chasing down the droids (more Doing) to a violent act of information gathering (Learning), which eventually leads to even more violent acts of Learning ("I think it is time we demonstrate the full power of this station...").

Plot Points and Inciting Incidents are not simply events that start a story and move it forward. Instead, it is best to think of them as fully integrated into the depiction of a single mind working through several different Concerns (here in Star Wars, Doing and Learning) as it seeks out an eventual solution (Understanding how best to fight the Empire).

The Matrix

The Inciting Incident of The Matrix is a little more difficult to track down.

And that's because the structural composition of a film like The Matrix is drastically different than a Star Wars.

The Matrix features a Main Character with a Female Mental Sex: Mr. Anderson/Neo prefers to manage relationships rather than engaging in any cause-and-effect problem-solving. Luke Skywalker is the dynamic opposite: he's all about problem-solving because Luke is a Main Character with a Male Mental Sex.

The differences between these two characters results in two completely different narrative structures. One of the standout results of a Female Mental Sex story is the complete lack of a traditional "inciting incident." This is because for the Female Mental Sex mind, time is flow and "problems" are never truly solved--they're justified.

We don't really know why Morpheus and Trinity are moving in the direction of Neo, we just know they are in that first sequence. While a Decision-driven story,

The Inciting Incident of The Matrix is Morpheus' decision that Mr. Andersen is the One they have been looking for (2/130). This one decision drives the entire rest of the story, for if he hadn't picked Tom the rest of the world would have stayed comfortably numb in their battery pods. Without the Inciting Incident, there would be no story.

Like most Holistic story structures, the start of The Matrix is less an on-screen "incident" and more a shift in direction of narrative inequities. We don't actually "see" Morpheus make any decision, instead only paying witness to the current direction (Trinity's opening fight with the various agents). The Female Mental Sex mind sees inequity--not problems, and therefore rarely registers an opening incident. Narrative structure must account for this reality (and does in Subtxt).

The First Act Turn, however, is apparent in Mr. Anderson's decision to take the Red Pill.

As with Star Wars, The Matrix begins the Objective Story exploration in Doing (chasing Trinity down, seeking out Neo, etc.). But whereas Star Wars veers off into conflict sourced from Learning, Neo's First Act choice of the Red Pill, spins The Matrix into an exploration of conflict centered about Obtaining.

Morpheus frees Neo's mind from the Matrix, Neo fails to make the first jump--leading everyone to question whether or not Neo is truly there to save the world (more Obtaining)--and then Cypher finally sells out his friends with his choice at dinner (an act of Obtaining that leads to Learning the team's whereabouts...).

It isn't until Neo finally decides at the end of the final Act that he is the One (121/130) that the problems in the story come to a successful resolution (a phone call where Neo wraps the final Act of Understanding with even more Understanding--a promise to "show them a world without you, a world without rules and controls, without borders and boundaries… a world where anything is possible.").

The Sixth Sense

The Sixth Sense actually repeats the same progression of Transits in the Objective Story (Doing to Obtaining to Learning to Understanding).

Sharing a similar opening shift in direction identified in The Matrix above, The Sixth Sense illustrates the potential for conflict in Malcolm's decision to treat Cole (Doing).

The First Act Turning point comes with Malcolm's request that Cole think about what he wants from their time together. When Cole responds with, "Can it be something I don't want?" the narrative shifts from simply treating (Doing) to securing peace and safety for Cole (Obtaining - 30/109).

The narrative of The Sixth Sense shifts into conflicts of Learning when Cole decides to reveal his secret, and then accelerates towards the end with Malcolm's decision to cease treatment--a mis-Understanding of the true situation that eventually leads to Cole mustering up the courage to choose to tell his mother the truth.

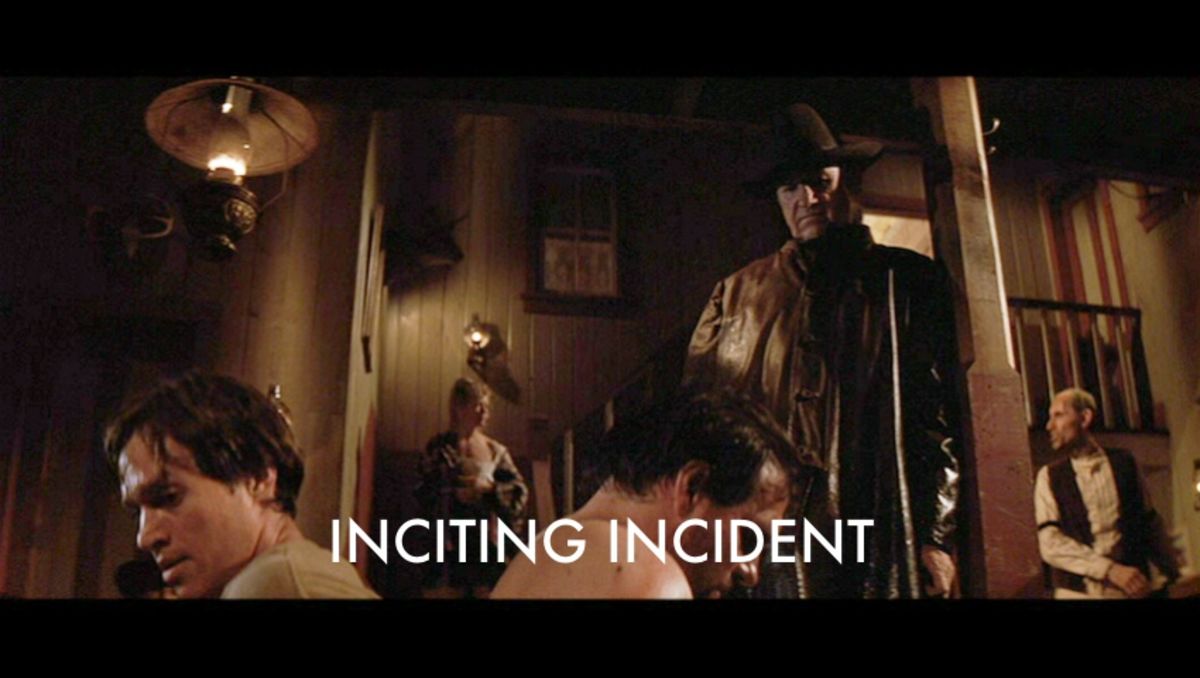

Unforgiven

The Inciting Incident of Unforgiven is Little Bill's leniency towards Quick Mike (5/120). Little Bill is known for dealing with criminals in his own special way, so why the sudden change of heart? His refusal to respond in kind creates a rift within the story at large--a conflict borne from mis-Understandings over how best to punish these men.

The women, now motivated by their appreciation of their lack of agency within the town (a potential of even more Understanding), seek out their own justice by hiring assassins.

The first Act Turning Point only makes matters worse with the arrival of English Bob and his refusal to surrender his sidearms to "proper authority"(33/120). Little Bill's abuse of English Bob is meant to send a message to other outlaws seeking a reward (a violent illustration of Learning).

With Understanding and Learning at the head of the Objective Story narrative, the only place left to go for the Objective Characters is Doing (killing the men behind the original act of abuse) and finally a clearing out of the town's bad seeds--leaving ownership of it all to those left standing (a final solution of Obtaining).

Casablanca

The Inciting Incident of Casablanca is Ugarte's decision to give Rick the letters of transit (15/127). While the murder of the two couriers seems to get things rolling, problems don't really start until Ugarte decides to give them to Rick. After all, people get murdered in Casablanca all the time. But give them to someone whose allegiances are in question? Now we've got a problem.

More than just a "Macguffin", these papers and the efforts to retrieve become the major source of conflict for everyone involved in the story as they strive to Obtain the letters of transit for themselves. This is why Rick's deliberations over what to do with them, including his refusal to help out Ugarte ("I stick my neck out for nobody"), propel the First Act into the Second (30-45/127).

With everyone now striving to find the whereabouts of the letters of transit, the conflict of the narrative shifts out of simply obtaining them and into Learning their location--a source of conflict that breeds interrogations and investigations that disrupt the tender balance within Casablanca.

The Lives of Others

Minister Hempf wants Georg Dreyman's girlfriend. The simple act of Obtaining begins with a decision to have Georg "watched." (10/135). Without this bigwig's desires, Weisler would have continued his life as he always had, and quite possibly would never have crossed paths with the writer and his friends.

Like Casablanca, the First Act Turn of The Lives of Others finds itself predicated by even more difficult decisions. This time it is Dreyman's best friend, the director Albert Jerska, and his constant ruminations over the purpose of his life that progressively complicate a simple spy operation into something far more reaching and grander in scope.

Jerska's dark considerations of suicide inspire Dreyman to write and to teach the rest of the world just exactly what is going on to artists behind the Iron Curtain (resistance to the initial potential of Obtaining in the form of Learning).

The Incredibles

The Inciting Incident of The Incredibles occurs with the overwhelming flood of lawsuits stemming from Mr. Incredible's loss in court against Oliver Sansweet, the man he rescued from suicide (14/127). This rush to sue forces the Supers into hiding, promising "to never again resume hero work." Previously costumed guys and girls now can't be who they want to be--initiating potential for a new kind of inequity.

While a Superhero flick on the surface, The Incredibles owes its unique narrative personality to its focus on the dysfunctional aspect of being a costumed savior instead of the typical focus on the physical nature of the job. This shift requires a completely different set of narrative concerns:

Instead the usual assortment of Doing, Learning, Obtaining, and Understanding, The Incredibles moves from Conceiving into Being, to Becoming, and finally into Conceptualizing.

The initial lawsuits kick off the idea that superheroes are a bad thing for a stable society (a conflict of Conceiving, or coming up with a new idea). If it had just been a singular idea, just Sansweet himself, then perhaps things would have simmered down and there would not have been a story. The flood of lawsuits, engendered by others getting the idea that they too could profit, tipped the scales and sent those with powers into hiding.

Problems escalate when Bob and Frozone almost get caught during the fire in the apartment building sequence (32/127). Before, Bob had found a way to deal with the initial problem by moonlighting with his best friend. This event, and their near apprehension by local authorities, forces Frozone to decide that this night was to be his last one. What was once a manageable problem has now become an even bigger one, eventually providing the motivation for Bob to accept the mysterious invitation from Mirage.

Those dysfunctional ideas in the First Act eventually drove Bob to take a job working for the opposition--and led to many moments of almost getting caught, as he pretended to be doing something else late at night (resistive pressure in the form of Being).

This alternate family of narrative Concerns help give The Incredibles that stand-out quality--a superhero film unlike most other superhero films. The acts of Conceiving and Being and eventually Becoming all come into being in the quest for an eventual solution, that can only be found in Conceptualizing. It's only when the individual family members figure out how they should all come together (an all-together new concept) that they finally subvert the dysfunctional psychology present from the very beginning.

Regardless of whether the conflict lies in the physical realm of Doing and Obtaining, or the more psychological domain of Being and Conceiving, plot points always drive a story towards the resolution of its initial inequity. That is the purpose of plot points...and the Inciting Incident.

Not Just About Movies

But what about other forms of narrative fiction? Surely this is just a "formula" for Hollywood-wannabes to follow...

Story is story regardless of medium.

The Inciting Incident of Shakespeare's Hamlet is the death of Hamlet's father. As with The Matrix, where the actual inciting event happens off-screen, the story of Hamlet immediately opens up with the characters plagued by the problem's effects:

HAMLET:

Let me not think on't! Frailty, thy name is woman--

A little month, or ere those shoes were old

With which she follow'd my poor father's body

Like Niobe, all tears--why she, even she --

O God! a beast that wants discourse of reason

Would have mourn'd longer--

Quick tranlsation: Hamlet has been thrown into great despair because of his mother's impulsive move to quickly marry his father's brother, Claudius (10%). The fact that she couldn't even wait a month drives Hamlet mad, thus creating a problem in Elsinore that calls for some sort of resolution.

As with The Incredibles, this exploration of madness calls for another family of narrative concerns:

Instead of the process-oriented explorations of physical or psychological conflict, the inequities in Hamlet fall into fixed mindsets. Memories and impulsive reactions (Preconscious) fight against the ego (Subconscious) and Conscious considerations. This former Concern is where Hamlet begins: why couldn't his mother mourn a bit longer?

This problem grows in importance when the Ghost of Hamlet's father informs his son of what really happened:

GHOST: A serpent stung me. So the whole ear of Denmark

Is by a forged process of my death

Rankly abused. But know, thou noble youth,

The serpent that did sting thy father's life

Now wears his crown.

HAMLET: O my prophetic soul! My uncle!

No longer an inequity that must be suffered, the death of Hamlet's father now becomes something that must be avenged (20%), and avenged immediately. The dramatic energy produced by the news of his father's passing has waned to the point where something new must come along and drive the story further towards its inevitable conclusion. This revelation of a "murder most foul" is that event, one that turns the course of events into the realm of the Preconscious--conflict stemming from impulsive responses and increased anxiety.

Problems, Energy, and Plot Points

Determining the events or decisions that escalate a story's problem should be Job One for the working dramatist. It is one thing to create an opening scene that wreaks havoc on the characters in the film and forces them to deal with this new problem, quite another to ensure that the inequity persists until the closing curtain.

Eventually, as with Hamlet, the potential for dramatic conflict will decline throughout the course of an Act. It is the same drop in potential that one feels as the pain from a pinch or slap in the face subsides over time. In order for the problem of a story to continue to drive the characters towards an eventual solution, a new potential must be introduced. These new dramatic forces, escalating the problem beyond that initial blast, drive the story forward in such a way that the characters themselves could never return to who they were or what they did during that first initial response. There can be no turning back.

Act turns exist to re-energize the potential of a story's problem, not to satisfy page-counting readers or paradigm-happy script gurus. Connecting the two first plot points to this problem, and making sure that they aren't simply the same event, will give an audience something to engage in and something to become invested in. The fact of the matter is that no audience member can resist the draw of the problem solving process as it unfolds on the big screen; it's human nature to see what greater meaning can be gained from how the resolution plays out.

Advanced Story Theory for this Article

Structurally, the Dramatica theory of story calls for four Acts, or Transits, in every complete story. Experientially (from the audience's viewpoint), the Journeys between these Transits are the Three Acts that most people (Aristotle included) feel when they watch or read a story. The Inciting Incident and First Act Turn surround that First Transit on either side. Dramatica smartly calls these plot points Story Drivers.

The problem with forcing the Inciting Incident closer to the 20 or 25 percent mark is that, from a dramatic perspective, there is little energy being spent during that first act. Typically, stories without a strong Inciting Incident also, by matter of definition, have no definable problem in place for the characters to deal with. Thus, no conflict and little for the audience to be concerned with. Waiting until the quarter mark to get things going is a surefire way towards creating a storytelling disaster.

The Inciting Incident exists, not because McKee calls for it, but because it creates that inequity in the lives of the characters within a story. There has to be some impetus for all that follows, some problem that needs to be solved. The Story Driver manufactures this problem.

And yes, I do mean page ZERO. In a perfect, computer generated world the Inciting Incident of a story would happen on page 0, with the following Act Turns happening every 25%. Thankfully, we don't live in such a world. ↩